Southern Staples

In honor of this artist’s Southern roots, this gallery includes prints that focus on classic southern wildlife. The Southeastern U.S. is one of the most biodiverse temperate regions in the world- but, a large portion of the Southeast’s biodiversity is not formally protected. This region’s biodiversity can be saved- but only if we can learn to appreciate & value it.

Dionaea muscipula

Sarracenia purpurea

Drosera brevifolia

Sarracenia flava

Carnivorous Plants

Step into a Carolina bog

Carnivorous plants are especially adapted for capturing and digesting insects and other animals. These plants tend to grow in acidic soils, that often lack crucial nutrients, like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. With the help of ingenious pitfalls and traps, these plants are able capture their prey and then utilize special enzymes to break them down. This adaptation of luring, trapping, and digesting prey give these plants and advantage over others that rely on soil alone for their nutrients. This carnivorous behavior has evolved independently about six times across several families and orders. The more than 600 known species of carnivorous plants, constituting a very diverse group, in some cases having little more in common than their carnivorous habit.

One of the most well-known and recognizable carnivorous plant is the Venus flytrap, Dionaea muscipula. Though Venus flytraps can be found for sale in most nurseries or even hardware stores, their natural habitat range is quite limited- with South Carolina being home to this famous species. Unfortunately, this species is still considered vulnerable to poachers who collect them with the intent to propagate and sell them.

This print features not only the famous flytrap, but also a handful of other carnivorous plant species that call South Carolina home, including: the purple pitcher plant (also known as turtle socks, or frog’s breeches), Sarracenia pupurea, the dwarf sundew, Drosera brevifolia, and the yellow trumpet pitcher plant, Sarracenia lava.

Carolina Bog Print

Carolina Bog- Prints 8" by 10", available in dark green & black ink

Carolina Bog Print

Carolina Bog- Print Series

Dolba hyloeus

Dendrophylax lindenii

Surprising Pollinators

an endangered orchid & multiple moths

In 2018, biologists spend countless hours tinkering in the tree tops, 90-feet above the ground setting up remote camera traps in Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge. With their total of 7,000 hours of footage, there were looking for the answer to one question: how does the ghost orchid, Dendrophylax lindenii, reproduce?

During this project, these biologists were able to document five species of moths visiting these ghost orchids. Up until then, it was only believe that one moth could pollinate this delicate flower: the giant sphinx moth. Now, with these photographs, it was shown that a couple of moth species other than the giant sphinx not only visit the ghost orchid, but also carry its pollen.

This print is to commemorate the first-ever photo showing a pawpaw sphinx moth (Dolba hyloeus) probing and pollinating a ghost orchid bloom. To learn more about this project, the biologists involved, and the new theories it spurred, read this National Geographic article.

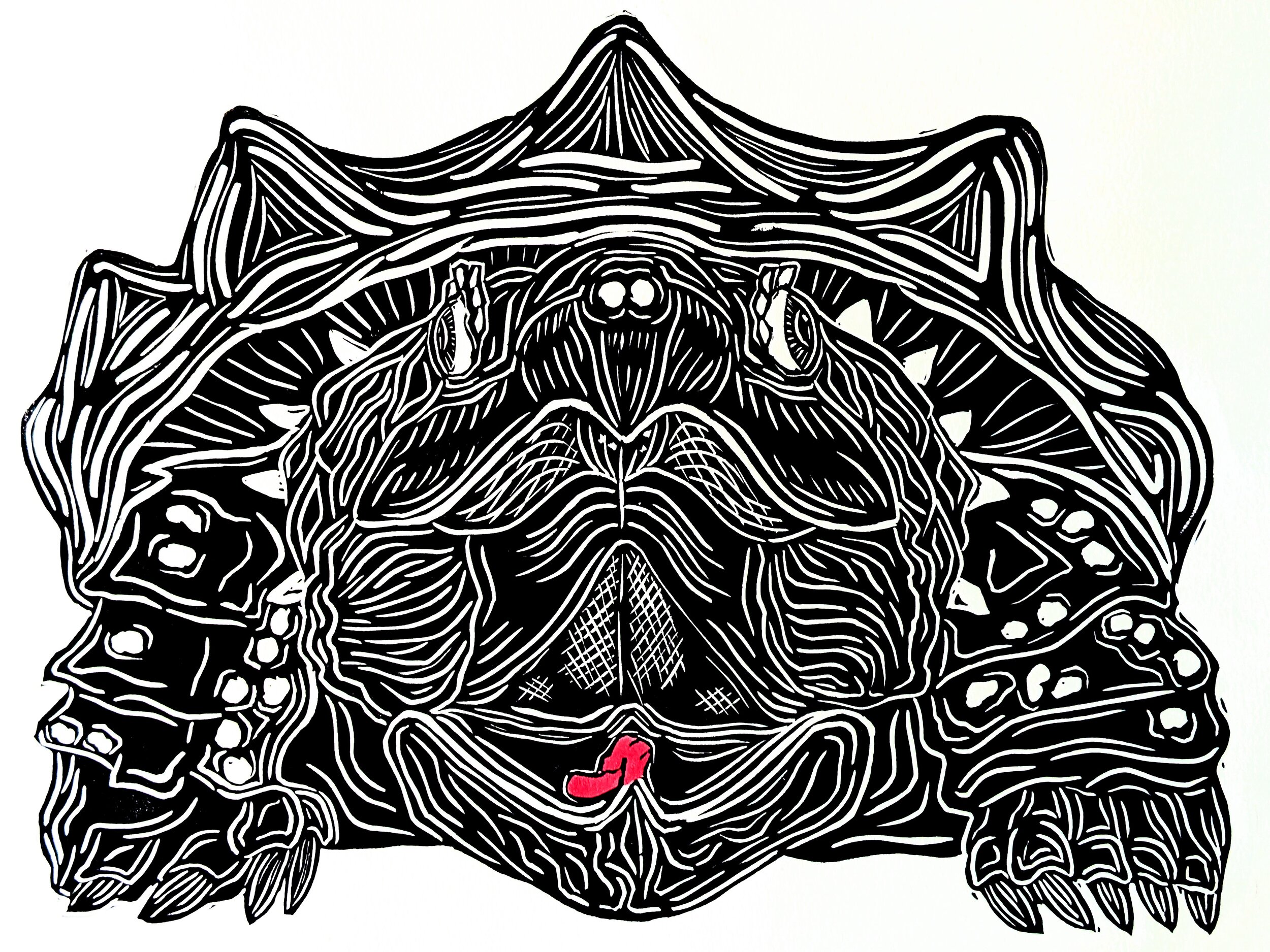

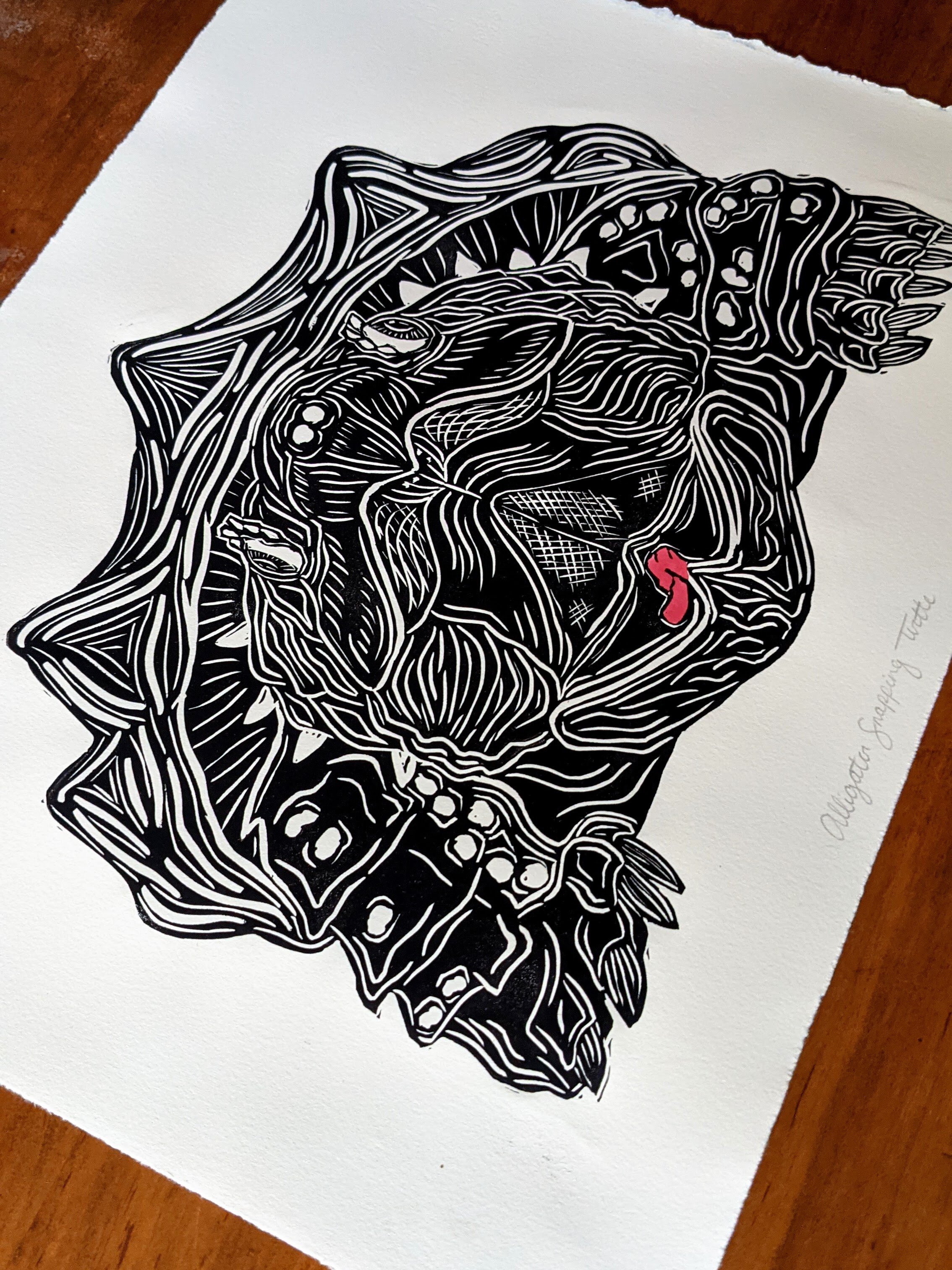

Alligator snapping turtle

Macrochelys temminckii

M. apalachicolae

M. suwanniensis

dinosaurs of the turtle world

Meet a prehistoric-looking predator: the alligator snapping turtle (formerly known collectively as Macrochelys temminckii, but has since been recognized as three genetically and morphologically distinct species). While they are the largest freshwater turtles in North America, alligator snapping turtles earn their name due to their unusually ridged carapace, which are reminiscent of the rough, rigid skin of alligators. This shell combined with finger-long claws, powerful beaklike jaws, and a thick, scaled tail creates a truly impressive creature.

Found almost exclusively in the southeastern United States, these snappers will spend the majority of their lives in the waters of rivers, canals, and lakes. The only real deviation from this habitat will occur when females travel inland (roughly only 160 feet inland) to nest. The average male can reach 26 inches in shell length and weigh upwards of 175 pounds (with females hovering around 50 pounds), and a few males have been known to exceed 220 pounds. While their size and appearance can be intimidating, they really aren’t all that aggressive (when compared to their relatives, the common snapping turtle).

In terms of hunting, they actually prefer to let their prey do most of the work. They sit passively still and simply let the fish swim into their mouths- sounds too easy, right? The alligator snapper actually has a unique adaptation within its mouth that allows this hunting technique to work: a bright-red, worm-shaped tongue. This unique natural lure allows the turtle to sit motionless on the river bottom, with its mouth wide open & tongue on display. As fish or frogs become curious of a potential easy meal, they come closer to the alligator snapper’s powerful jaws and become a meal themselves.

Alligator snapping turtles can live to be between 50 to 100 years old. While adult snapping turtles have no real natural predators, their population has been severely reduced due to unregulated harvesting by humans and habitat degradation. This has resulted in them being listed as Vulnerable and has led to statewide protections throughout most of their range.

Alligator Snapping Turtle Print

Alligator Snapping Turtle Print

Alligator Snapping Turtle Print

Print Process- Sketch, Block & Print

Salamanders

Order Caudata

amazing amphibians

Salamanders are included in the group Caudata- an order within the class Amphibia- that contains about 740 species of amphibians (including newts, blind eels, and other related forms). The name Caudata relates to the word “cauda”, meaning “tail” in Latin. This is because animals in this order are characterized as having long bodies, long tails they retain throughout their life, short & weak limbs, and feebly ossified crania. The order comprises 10 families, among which are newts and salamanders proper (in the family Salamandridae) as well as hellbenders, mudpuppies, and lungless salamanders. Primarily in temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, salamanders are commonly found near fresh water and damp woodlands, due to their reliance on water as an integral part of their life cycle. Below are two salamanders found in the southeastern United States: the Spotted Salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) and the Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber).

spotted salamander

Ambystoma maculatum

Spotted Salamanders are large salamanders that are found throughout eastern North America, and are common in the Piedmont and Mountain regions of South Carolina and Georgia in hardwood forests and swamps, where they have reliable access to water. Ranging between 6 to 9.5 inches in length, these salamanders are shades of black, gray, or brown with rows of yellow/orange spots down their back. (Sometimes, there can be as many as 50 spots!)

These salamanders are fossorial (meaning they burrow), are active at night, and are rarely spotted except during their breeding season when adults migrate from their burrows to pools during the winter rains. Adult spotted salamanders can live up to two decades-long.

While this species is considered common and is unprotected in most regions, the destruction of temporary wetlands and forest alterations pose a potential threat to this species’ future.

Spotted Salamander prints

5" by 7" Spotted Salamander print- dark purple and yellow ink on cotton rag paper

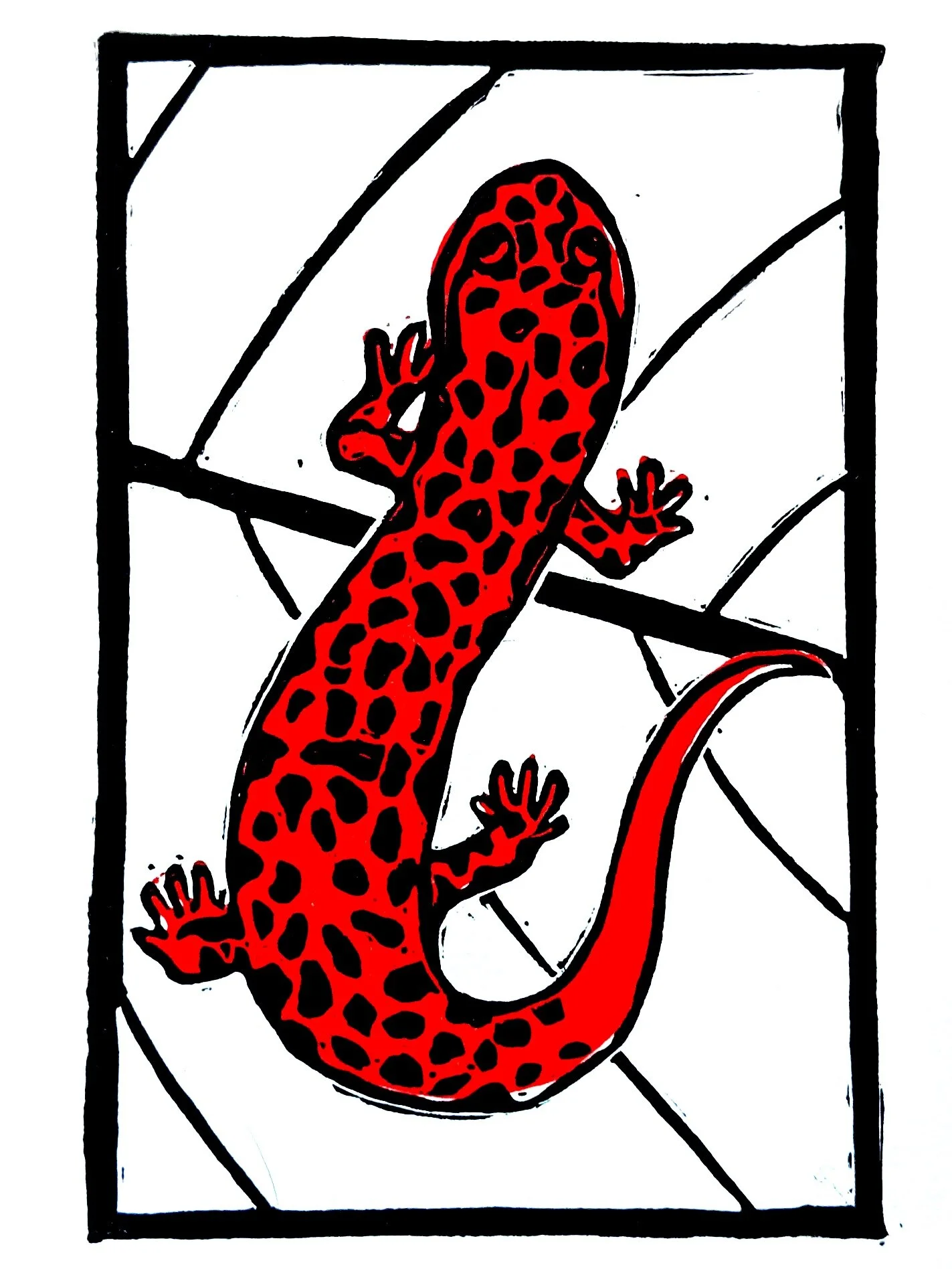

red salamander

Pseudotriton ruber

This salamander is found throughout much of the eastern United States. It belongs to a family of lungless salamanders (Plethodontidae) that breathe only through their moist skin. Although this may seem to be a handicap to their survival, there are actually more species in this family than in any other family of salamander.

Red salamanders can range between 4 to 6 inches in length and are very stout with short tails, compared to other salamanders. They are a bright red to reddish-orange with many irregularly rounded, black spots along their back. While they can be found in a variety of habitats, they are most common around streams, springs, and small creeks- though, adults can wander farther upland into forest habitats, returning to the water to breed and lay eggs in the late summer/ early fall.

During the day, these salamanders will take cover under rocks, logs, and other objects near streams or seeps. At night, when they are most active, they search for invertebrate and small vertebrate prey (and, in some regions, the bulk of their diet will actually consist of other salamanders).

While this species is considered common and is unprotected in most regions, the destruction of temporary wetlands and forest alterations pose a potential threat to this species’ future. In addition to the threat of habitat destruction, adult Red salamanders are frequently found crossing roads on rainy nights, which can place them in danger of vehicular damage.

Red salamander prints- red & black ink on cotton rag paper

Variation in prints due to hand-pressed layered blocks

Red salamander print- 5" by 7"

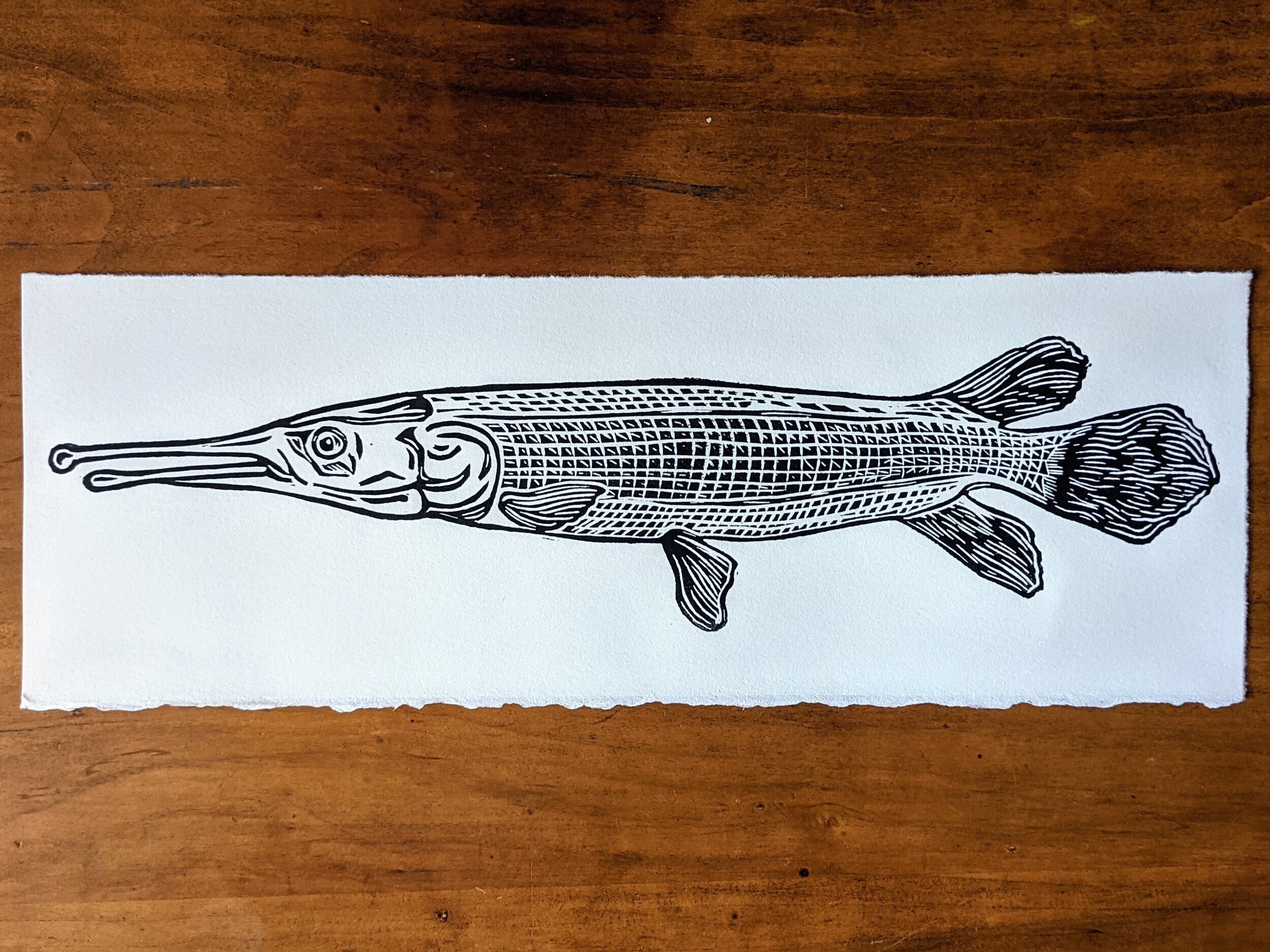

the alligator gar

Atractosteus spatula

anything but a “trash fish”

Meet the largest member of the gar family, and one of the largest freshwater fish in North America: the alligator gar. While it bears no relation to alligators, the name acts as a tribute due to this fish’s razor-sharp teeth and wide, crocodilian head. Alligator gars have had a historically wider range throughout the southern US, however now they are known only to live in the lower Mississippi River Valley, from Oklahoma to the west, Arkansas to the north, Texas and portions of Mexico to the south, and east to Florida. While they tolerate brackish waters, and even some saltwater conditions, they prefer the backwaters of large rivers, swamps, bayous, and lakes.

Although they may look ferocious, alligator gars pose no threat to humans and there are no known attacks on people- there is only one passive danger: their eggs. The eggs of an alligator gar are poisonous to humans if eaten. This toxicity is believed to serve as a defense mechanism against predators.

In the past, alligator gar have developed an unfair reputation for being a “trash fish”- primarily because anglers believed they damaged nets and devoured their game fish. While these gars do primarily prey on fish, they are opportunistic feeders who also eat blue crabs, small turtles, waterfowl or other birds, and small mammals. Throughout the 20th centuries, resource managers would often recommend culling the gars to protect populations of game fish- resulting in their population numbers plummeting and only stable populations existing in Texas and Louisiana. However, biologists have been working to repair this damaged “trash fish” image by demonstrating that the alligator gar presents no real danger to game fish populations. These fish are now protected under state laws in its range, and there are even plans to reintroduce these fish back into the waters where they were historically found.

Print size: 12 inches by 4 inches

American Woodcock

Scolopax minor

A plump shorebird with a funky strut

Known by many names, the American Woodock (Scoloplax minor) is also referred to as the timberdoodle, Labrador twister, night partridge, and bog sucker. Unlike its coastal relatives, this plump little shorebird lives in young forests and shrubby fields in eastern North America; it’s brown-mottled plumage camouflaging perfectly against the leaf litter.

The American Woodcock has an unmistakable strut, as it slowly moves along the forest floor, probing the soil with its long bill in search of earthworms. It walks slowly, sometimes rocking its body back & forth, stepping heavily with its front foot. It is believed that this action might make worms move around in the soil, increasing their detectability.

These birds are notoriously difficult to catch sight of- unless, it is in the springtime at dawn or dusk, when the males show off for the females by performing aerial displays and giving distinct nasal calls. With both sexes being roughly the same size, the average American Woodcock ranges between 9.8 - 12.2 inches and weighs between 4.1- 9.8 ounces. (The Cornell Lab)

Print size: 11 inches by 14 inches; Life-size American Woodcock

The Great Eastern Brood

2021 Brood X cicada emergence

While cicadas are a constant fixture in the southeast, 2021 promised an entomological marvel: the emergence of billions of cicadas across the eastern United States. Known as the Great Eastern Brood (or, Brood X), these insects are part of the largest emergence event since 2004, with an expected geographical range stretching from Tennessee to New York.

These cicadas have been underground for 17 years, tunneling and feeding beneath the soil. When they emerge and are back above ground, they will start the search for a mate. It’s this search that prompts the males to create a loud, buzzing sound by flexing a drum-like organ called the tymbal: it’s a mating song.

Worldwide, nearly 3.400 species of cicada exist- but periodical cicadas (like Brood X) that emerge in mass amounts once every 17 or 13 years are unique to the eastern US (with 13 year cicadas being more prominent in the South and Mississippi Valley).

The three 17-year cicada species- Magicicada cassini, Magicicada septendecula & Magicicada septendecium - all have similar appearances, with black bodies, orange/gold wings and red eyes. But, there are smaller differences in the details of their overall size, shape, color, and song.